Pat and I met later in Dublin. I liked him immediately, and he had a film in mind. I wasn’t interested until Pravina and I had finished our book Sacred Art. We had to return to Brazil, in 2018, to give copies of the book to all the artists in it, and I thought how good it would be to have patient, professional footage of the artists at work.

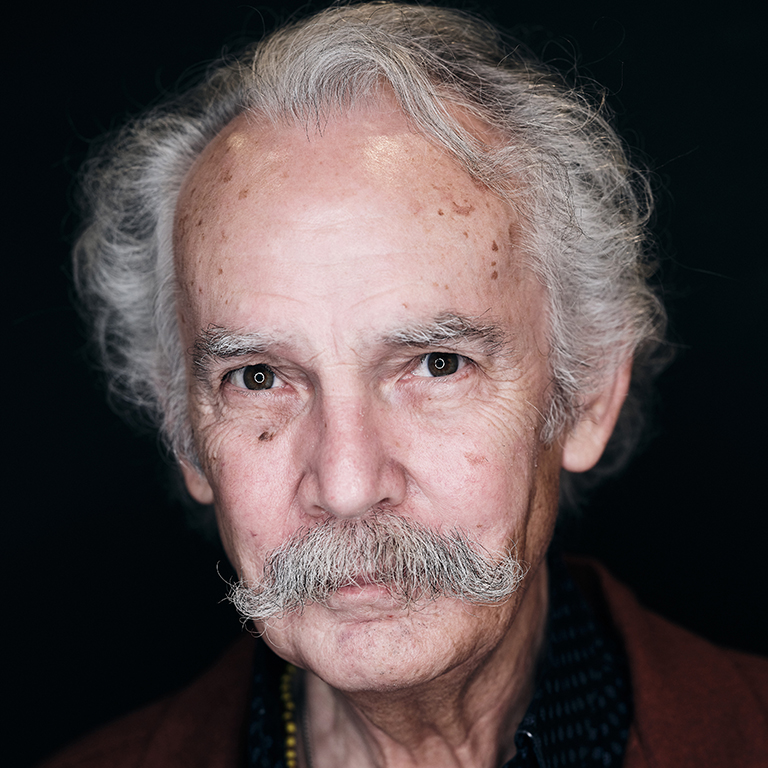

We met up in Salvador. Pravina and I had gone earlier to explain the film to our friends, the artists. Pravina was raised in Brazil, speaks Portuguese like a native, and she and I fade easily into the crowd. Pat arrived with his crew: his cameraman Colm Hogan, Colm’s assistant Roman, and Bob Brennan the soundman. With their van and cumbersome, abundant machinery, they created a conspicuous presence. All was unfamiliar, the heat, the vast city of beautiful black people, but they were brave, unflustered, quick to adapt, and always good company.

The film begins in Maragojipinho, a pottery town beside a calm river in the interior of Bahia. A flurry of work is followed by slow, close attention to Rosalvo Santana shaping clay into an elegant image of Nossa Senhora Desatadora dos Nos. The scene shifts to the city, to Nilo dos Santos making a woodblock print of Orunmilá, the Yoruba god of wisdom. Then, in my favorite bit, Samuel welds junk into a statue of Oxóssi, the Candomblé lord of the hunt. Salvador ends with our close friends, Edival who carves and Izaura who paints statues of the saints that are carried in processions through the streets and placed on the high altars of baroque churches.

Later that summer we met up in North Carolina, where I had a field project in progress, so Pat and his crew could film the potters, our friends Mark Hewitt and Daniel and Kate Johnston. The crew caught Mark at firing time and they filmed Daniel making a robust big pot with the technique he learned in Thailand.

Communications swept back and forth across the Atlantic. The film kept getting better. Pat used my photographs and snatches of a video by Tom McCarthy so Turkey, where I had done a decade of fieldwork, could be part of the story. Ahmet Şahin, one of the greatest ceramic artists of modern times, makes a touching appearance. Young women from the Öztürk, Balcı, and Kurt families in the mountains bring color to the film with their magnificent carpets.

For the final filming we were back in Ireland in March of 2019. We walked the lanes of Ballymenone, and I sat in Blake’s of the Hollow in Enniskillen to remember my hero Hugh Nolan. Then Pat worked hard to finish the film that had its world premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival in September of 2019.

Pat couldn’t make it, but Tina O’Reilly, the producer, came, and she and I and Pravina did the best we could with all the interviews. After the screenings, we weren’t congratulated by elderly folklorists but by youthful filmmakers who, certain they didn’t want their own films to look like television or Hollywood, found in Pat’s film an inspirational alternative.

Before it is released, the film has to roll through the cycle of film festivals, a cycle the pandemic has interrupted. Screenings planned for the spring at the RiverRun festival and in Indiana University’s cinema series were canceled. Pat Collins, as I write, still hopes for an Irish premiere at the festival in Galway, to be followed by an Irish tour, screenings in small communities to provoke discussion about local tradition. But, considering the usual fate of the best laid plans of both mice and men, who knows?

The College of Arts

The College of Arts